A Brief History of Meditation

What is meditation?

In its broadest and most universal definition, meditation is a discipline that involves turning the mind and attention inward and focusing on a single thought, image, object or feeling. Meditation is sometimes called attention regulation (or attention training). Various meditation practices can be further defined according to the object of meditation, whether the mind is focused on the breath, the mantra, the body, a deity, or an attribute like stillness, peace, love, etc.

The goal of meditation varies according to the technique that is practised. Some techniques instil peace, some reduce stress, bring insight or enlightenment, some instil confidence and creativity, some work with thought and feeling patterns, some answer the most basic and mundane questions, some answer the most soul-searching and mystical questions, and some do it all.

It is difficult to trace the history of meditation, but there were several seals dating to the mid 3rd millennium BC, discovered in India at Indus Valley Civilization sites. They depict figures in positions resembling a common yoga or meditation pose, showing “a form of ritual discipline, suggesting a precursor of yoga,” according to archaeologist Gregory Possehl. Historians also know that techniques for experiencing higher states of consciousness in meditation were developed by the shamanic traditions and in the Upanishadic tradition of Hinduism.

Originally meditation practices were largely aimed at spiritual enlightenment, a central part of which was the alleviation of suffering. Since then the practice of meditation has traversed virtually every culture and religion, although a rise in materialism coincided with a decline in spiritual practices. The beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th C caused a lapse of interest in meditation in the Western world.

Meditation in the West

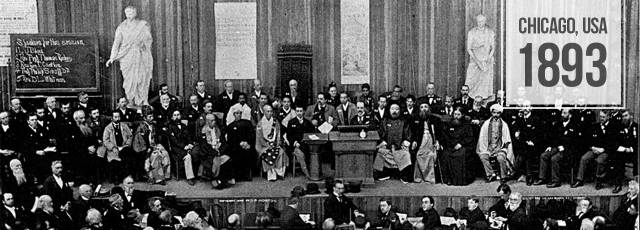

From the moment Swami Vivekananda of the Ramakrishna mission walked onto the stage, at the first Parliament of World Religions in Chicago, Illinois in 1893 to a standing ovation without having spoken a single word, meditation has both attracted and mystified the Western world. He had so much gravitas that the audience of over 8,000 people from all over the world sat enthralled at every word he spoke. He was the first of many spiritual teachers to venture West from the East to spread the teachings of meditation to a hungry public. His influence is still felt today.

1893 Parliament of World Religions

Perhaps the earliest noteworthy Western contributor to meditation in the early part of the twentieth century, was the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung who explored and drew upon Yoga and other Eastern philosophies and practices in forming his ideas.

However, in the 60s and 70s a meditation revival began with the advent of Hindu and Buddhist teachers travelling the Western world teaching Hatha yoga, Kundalini Yoga, meditation, Zen, Dzogchen, Sufism, Tibetan and Mahayana Buddhism, Advaita Vedanta, the yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Kashmir Shaivism, and other philosophies.

Hence, Western contemplative traditions have largely been influenced by Eastern Gurus, both Hindu and Buddhist. Experimentation with meditation grew significantly during this period, especially in America as the practice of Yoga took on new significance. Meditation began to find its way into a Western vernacular.

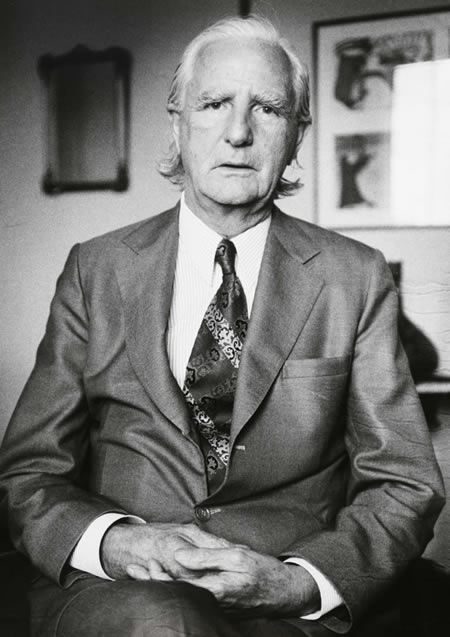

Ainslie Meares

Mental Rest for Anxiety Relief and Stress Management

As Hindu and Buddhist teachers were travelling West, a number of Western thinkers were travelling East in search of enlightenment and to study Eastern philosophies; so modern relaxation techniques and a variety of concepts of meditation began to emerge. The German psychiatrist Johannes Schultz created the relaxation technique and Autogenic Training while an American physician named Edmund Jacobson produced Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). Both of these ideas are still popular today. In 1963 the Australian psychiatrist, Ainslie Meares (pictured) published his Atavistic Theory of Mental Homeostasis, pioneering the concept of therapeutic meditation (now known as Stillness Meditation Therapy) for the treatment of anxiety and pain. Later, he applied Stillness Meditation Therapy to the management of cancer. In the early 1970s the Transcendental Meditation (TM) movement popularized meditation to a wider audience and was influential in fostering some of the early research activity.

In the late 1970s American medical biologist, Jon Kabat-Zinn integrated Buddhist teachings with Western science to establish Mindfulness Meditation for the purpose of stress management. In recent times his work has influenced research into meditation as a healing modality. In the 2000s there has been a literal explosion in interest in the clinical and research applications of meditation, much of this being fostered by the Mind and Life Institute.

While all meditation approaches involve relaxation of body and mind, different styles may be used for individual preference or purpose.

Stillness Meditation Therapy: Meares’ theory in 21C

In contrast to the general description of meditation set out above, the Ainslie Meares theory of meditation does not advocate focus or attentive techniques but emphasizes the importance of mental rest. In 1983 Melbourne author and psychotherapist Pauline McKinnon was invited by Meares to promote this unique therapeutic meditation as a secular health practice for the management of stress, anxiety, pain and related conditions.

Stillness Meditation Therapy (SMT) is physiologically based and non-sectarian. It is significantly different from traditional meditation and it has no affinity with Mindfulness Meditation.

In Meares’ view, the experience of stress increases impulses to the brain, creating sensory overload, which then leads to elevated anxiety. His solution to anxiety and related discomforts is “psychic equilibrium” through activation of the natural, moderating homeostatic mechanism. This, according to Meares, is achieved through atavistic regression, a biologically primitive and profound level of mental rest. Meares’ Stillness Meditation Therapy accomplishes this aim through a meditation of utter simplicity – the effortless experience of one’s own inner calm.

In summary, when communicated authentically, SMT is a method of effective therapeutic meditation for the modern world:

- The mind is rested naturally without the activation of technique

- Reactivity converts to calm in the face of discomfort

- Anxiety and associated symptoms are relieved

- Living calm leads to better health

- Therapeutic value is enhanced by sessions with a trained SMT teacher

Meditation for enlightenment

The significant aspect of Eastern philosophies is that they give asadhana, a means for ending suffering and attaining peace. Practices and techniques can be applied in every circumstance. Most importantly, there is a technique and practice for every type of person.

The Buddha was the first major Hindu Guru who influenced the rise of meditation in India. Traditionally Brahmin priests acted as intermediaries between the individual and the Absolute. The Buddha’s teaching broke with this tradition. The individual could now discover ‘illumined mind’ or higher Consciousness within.

The Buddha’s teachings pervaded Asia and now they have permeated Western culture as well. Teachers of Zen, Mahayana, Tibetan and Theraveda traditions, like Suzuki Roshi, the Karmapa, SN Goenka, Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, the Dalai Lama, Kalu Rinpoche, Chogyam Trungpa, Sogyal Rinpoche and others have continued the Buddha’s teachings and established meditation centres in the West.

The idea of Enlightenment has been a natural part of Buddhist and Hindu society since it began. Gurus, meditation, and spiritual philosophy are a natural part of a Hindu family’s life. There have been many Gurus, even before the Buddha, throughout history that have attained enlightenment, taught the path to others and transformed lives.

More recently in the 19th and 20th C the influence of HIndu gurus such as: Ramana Maharshi, Guru Maharaji, Swami Satyananda, Satya Sai Baba, Swami Yogananda, Krishnamurti, Swami Muktananda, Shivaya Subramuniyaswami, Swami Chinmayananda, Nisargadatta Maharaj, Osho, Anandamayi Ma, Bhagawan Nityananda and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, still resounds in the Western world.

The spiritual paths laid down by Gurus include achieving a higher state of consciousness or enlightenment, understanding and connecting to the inner Self, awakening to a higher power, developing and increasing compassion and loving-kindness, and receiving spiritual inspiration or guidance from the Self, God or the Guru.

Meditation and self-development

Not only was there an influx of meditation during the 60s and 70s but psychology also took on new meaning as a transpersonal element entered the culture. Suddenly everyone wanted to ‘raise their consciousness.’ Innovators like Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, Roberto Assagioli, Oscar Ichazo, Virginia Satir, Werner Erhard and others offered a simpler and practical understanding of the mind and the emotions compared to Freudian Analysis. Many were students of Jung who was influenced by Hindu teachings such as the Upanishads, and expanded on his ideas. Therapists began to use art, the breath and psychodrama as a means of clearing emotional ‘baggage’.

Developing and working on oneself as an integrated person in order to achieve full potential as a human being became more acceptable as a way of handling inner struggle. More and more Western thinkers sought ways to deepen their understanding of how the mind and the emotions worked.

Meditation as a secular practice

Although traditionally practised as a spiritual discipline, meditation in the modern context has gained valid attention because of the mental and physical health benefits associated with its practice. Today, certain forms of psychotherapy are also associated with meditation. Thus different meditative disciplines encompass a wide range of spiritual and non-spiritual goals.

In more secular, therapeutic or personal development contexts, the benefits of meditation include achieving greater focus and improved performance, enhancing creativity or self-awareness, cultivating a more relaxed and peaceful frame of mind, managing chronic pain, depression and anxiety, and providing a range of physiological and metabolic benefits for the cardiovascular, immune and neurological systems.

What is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness meditation has a long history in spiritual traditions and more recently as a secular practice that has entered the mainstream. Professor Jon Kabat-Zinn and his Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, launched at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in 1979, has been the most influential mindfulness teacher around the world. In the following piece, Melbourne Mindfulness expert and ATMA Patron, Dr Craig Hassed explains:

A simple way of defining mindfulness is ‘a mental discipline aimed at training attention’. There are other implied aspects of it, for example, mindfulness-based practices:

- generally utilise the senses as a point upon which to train the attention.

- engage the mind in the present moment.

- foster self-control through non-attachment to transitory experiences like thoughts, feelings and sensations.

- encourage an attitude of openness, curiosity, acceptance and non-judgementality.

- cultivate equanimity and stillness through being unmoved by, or less reactive to, moment-to-moment experience.

Training one’s attention in this way is generally called mindfulness meditation. There is nothing particularly Eastern or Western about mindfulness or meditation. The present moment, the mind, the body, and attention don’t have an east or a west.

Meditation can bring with it certain expectations, such as being able to ‘blank out’ one’s mind, or to get rid of thoughts but the mind often continues to think even if we don’t want it to so even when the mind is still active we can learn to be mindful of thoughts without being involved in them. Mindfulness implies an attitude of curiosity, openness and acceptance of, rather than reactivity to, whatever is happening. Non-reactivity doesn’t mean not responding, it just means that we don’t feel so compelled to react especially without choice and discernment.

Mindfulness is not just about meditation, it is also a way of living and a foundation for psychotherapy. The aim of mindfulness meditation is to be increasingly able to take that same attentiveness and attitude into our day-to-day life so that we will not only feel better but also learn, function and communicate better as well as grow in wisdom.

Meditation, Physiology and Psychology

Meditation techniques have been incorporated into a range of counseling and psychotherapy approaches, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). Originally used with systematic desensitization, relaxation techniques are now used with other clinical problems. A range of other techniques and forms of psychotherapy such as hypnosis, biofeedback, Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), EMDR, and multimodal therapy all employ the use of meditation as an individual therapy technique.

The side effects of meditation include the relaxation response that works toward achieving mental and physical relaxation to reduce daily stress. This reverses the increasingly common and deleterious effects of the chronic over-activation of the stress response (known as high ‘allostatic load’).

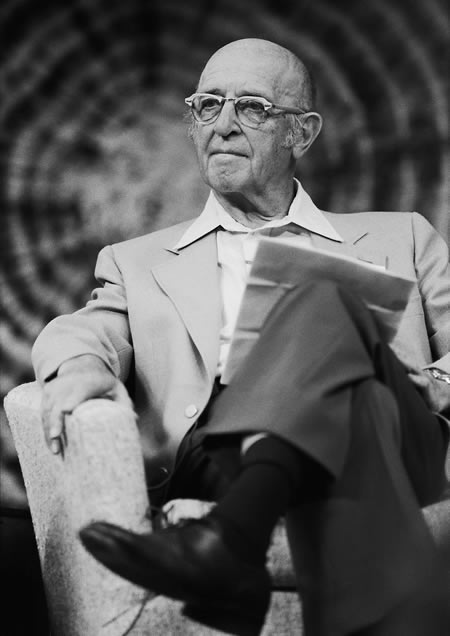

Carl Rogers

From the point of view of psychology and physiology meditation can induce a heightened state of consciousness – i.e. it raises awareness. Relaxation, concentration, an altered state of awareness, a suspension of discursive thought, and the maintenance of a self-observing attitude are sometimes cited as the behavioural components of meditation. It is also accompanied by a host of biochemical and physical changes, such as altered metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, immune function, genetic function and repair, and brain anatomy and function.

Meditation has been used in clinical settings, but its use in the mental health and emotional regulation settings have probably created more interest than any other single field. Other areas of application include the enhancement of performance in sporting, business and academic settings. From a spiritual or philosophical perspective, the physical, behavioural and psychological benefits of meditation could be seen as ‘side-effects’ rather than the central aim of the practice.

The Future of Meditation

Meditation continues to expand in every culture around the world. An American survey in 2007 showed that over 20,000,000 people had either tried meditation or were meditating. The Canadian government did an experiment in a large business and found the group that meditated produced more dollars, worked more efficiently and were happier in comparison to the control group who did not meditate.

Since the advent of meditation in the West there have been and are now many Western spiritual teachers from every tradition who have taken up the mantle of spreading meditation around the world. There is no doubt that the number of Western teachers will continue to grow and adapt meditation to suit a Western audience.

In 1977, one Hindu yogi said that if 1% of a population of more than 10,000 people practised meditation it would have an impact on the collective consciousness of a society. This impact, he posited, would result in a reduction of violence in the community and of armed conflict throughout the world.

When we commit to a meditation practice it not only alters the chemistry of our own thoughts and feelings but it can positively affect those around us. The energy of meditation builds within us as we practice and the happier and more peaceful we become, the more positive our life becomes.

Meditators understand the enormous benefits of a meditation practice and are eager to share this knowledge with as many people as possible. When we begin a meditation practice we are joining a worldwide community of people who are committed to peace, love, wisdom, compassion and joy. We encourage you to join us.